Rules-light games are all the rage these days. A search for "rules-light" on Drive Thru RPG (an online RPG store) returns 13,194 hits! Certainly, game designers are thinking about making simpler games, and there are good reasons for it. For starters, rules-light games are easier — easier when introducing newbies to TTRPGs, easier for even veteran players to learn, easier if you want to try a bunch of new games. And, let's face it, a rules-light game is easier to make. Heck, a game designer making ten rules-light games is more likely to get a hit than with the one complex game that would take the equivlent time and effort.

I would argue that on the whole, D&D Fifth Edition is a rules-light version of the game. Fewer rules, fewer choices in creating characters, easier leveling, compared with Third Edition. Look at how 5E has fewer skills. Look at how infrequently your attack bonus and saving throws change. Look at how there are fewer rules covering fewer situations in 5E.

Look at senses, for example. Third Edition has low light vision, darkvision, blindsight, blindsense, tremorsense, and scent. Fifth Edition lost low light vision, blindsense, and scent. Fifth Edition combined Spot and Listen into Perception. No more detecting evil or good. Fewer options for divinations generally.

Now, there is certainly an argument for simplicity in rules, especially if the alternative is kludgy, arbitrary, and whimsical. Third Edition (and Pathfinder) had too many magic systems: prepared spells, spontaneous spells, ki, grit, psi, and on and on. A single unified magic system is a simpler solution, and I've implemented something like that in Labyrinths & Liontaurs.

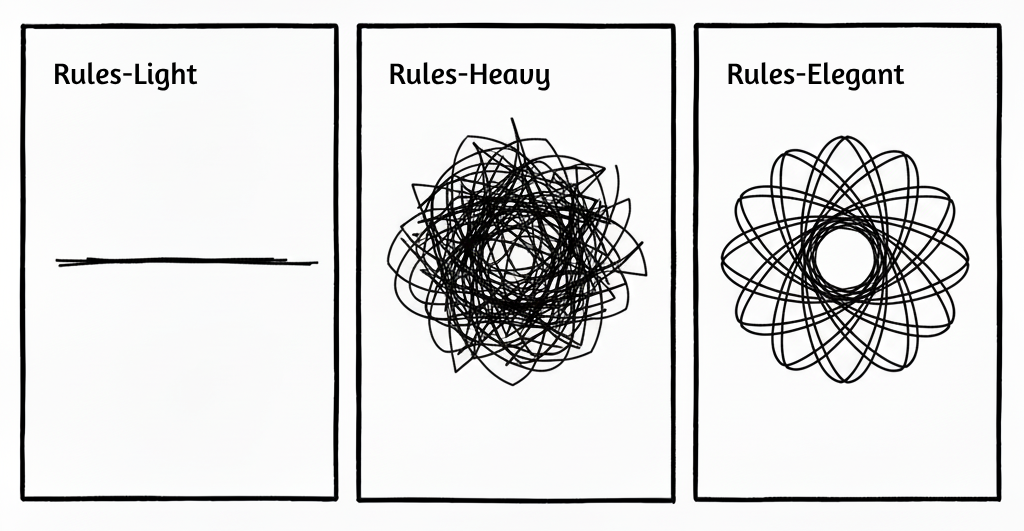

But the choice is not a binary: simple vs complex, light vs heavy. The third option is rich and elegant. A well-designed dense system can be relatively easy to learn and run, especially if it is internally consistent, clearly written, and makes rational sense. Let's look at my own game and the ways it is rich, offering substantial choice, and elegant.

Rich and elegant games expand the possible modalities of play. L&L tries hard to give equal weight to exploration, interaction, and combat. Take skills, for example. Skills are a primary way to do more outside of combat. L&L, even more than 3E, offers many skills, and devotes deep rules and options for these skills. 5E narrows the number of skills tremendously, and gives only a short sentence to describe their use and the opportunities they allow. Compare with the 5E rules for weapon mastery, with dozens of lines of text intended only to enhance combat options.

You can argue that a character can do exactly the same things with their skills in both 3E and 5E. It is just that 5E relies a LOT harder on game master adjudication and interpretation. But is that really true? In 3E you can use Bluff to send a secret message or to gain an advantage in combat. Would a typical 5E game master allow that with 5E's deception skill? A rich set of rules offers more possibilities, suggests ways to use rules, and evens out the game experience, whether your game master is generous and improvisational or uncertain and unwilling to experiment.

The rules of the game push the players and masters towards the style of play and the options that the system intends. In a simple game, they limit horizones. In a rich game, they give the game master ideas on ways to play. Would you even think of putting a hurricane in a game with no weather rules? would you add golems to a game that had none? And if you did think of that, you would have to find or create your own mechanics for them.

Rich and elegant systems foster fully realized worlds and long-lasting campaigns featuring long-running characters. Yes, an inventive, story-teller-type game master can use the simplest rules-light system to create and run an deep, complicated, narratively compelling campaign over many sessions. But most rules-light systems are not intended for that. And most game masters are not genius-level world-builders and story-tellers. On one hand, they include mechanisms for character advancement that can satisfy gamers over a very long haul. On the other hand, the amount of work involved in creating a rich, dense, elegant game in turn inspires game designers to create many modules, settings, adventure paths, and expansions. These rich games see years and years of play, while many rules-light games are lucky to get a second session.

In Labyrinths & Liontaurs, The game is intended to give players meaningful choices every level. Each class offers a choice of class ability every level, and a non-class choice (feat, trait, ability score boost, or racial power) as well. In 5E, the biggest choice comes at level 3, in choosing a subclass. After that, a few levels offer a choice of feat. And those are the levels that are the most interesting. But much of the time, levelling is simple, and easy, because every fighter 5 is the exact same as every other. In some games *cough*Pathfinder2.0*cough* this kind of choice would be a hot mess, a tangle of options that serves confusion and power-gaming. But L&L forces choices in a balanced mix of game modes: At character level 2, everybody gets a social-oriented power; at level 3, a combat power; at level 4; an exploration power. And that pattern repeats at levels 7, 8, and 9; at levels 12, 13, and 14; and at levels 17, 18, and 19.

A rules-light game need not worry about any of that. Such a game is not intended to offer deep immersive variations, combinations of rich options, that will keep players engaged for years of play.

Rich and elegant mechanics allow the parts of a game to fit together easily and beautifully. The prime example here is multiclassing. In 1E, saves and attacks did not stack across classes: a fighter/ranger used either fighter bonuses or ranger bonuses, not both added together. In 3E, combining classes was very hit or miss. Some combinations were powerful; others we not viable. 3E multiclassed warriors at least had the common interoperability that base attack and saving throw bonuses stack, but with incompatible magic systems, 3E multiclassed spell casters were basically screwed. The problem was poorly patched with prestige classes such as the Mystic Theurge, but that did not much help your bard10/druid10, an extremely underpowered build (and a complex hot mess).

My solution, in L&L, is to stack caster level. All casters cast alike, using 3E's spontaneous casting, spell slots, and known spells list. That interoperability makes it much easier to stack casting. Simply add all caster levels together to determine spell slots per day. and just as all classes have a base attack bonus, which contributes to one's combat potential, so all classes have a caster level, all classes cast spells, all classes contribute to caster level.

A word about math. One element that most tabletop RPGs feature is rolling dice. That means numbers: comparing numbers, adding and subtracting numbers, writing down numbers, and learning what numbers are good and what are bad. Yes, a few rules-light games are math-free, and more power to them. But to me, math is an essential part of a rich roleply game.

And that's a good thing! There is a joy in rolling a natural 20, or even in rolling a natural 1 — once in a blue moon, one hopes! That's one thing that makes for stories that last through the years. And part of the fun is seeing your numbers advance: your character wealth increase, your character level rise, your saving throws getting better. And that means math! Embrace it!

But some games are too math-phobic. 5E so hates math that it has de-emphasized many bonuses and penalties to rolls by replacing them with advantage and disadvantage. It is easier to apply this mechanic than to account for a miss chance due to mist, a flanking bonus, an aid another bonus, and the bard singing encouraging words. The problem is that advantage/disadvantage is a hammer. A sledgehammer! It is too powerful. As a player, you strive to have advantage whenever you can. And if you have disadvantage, you might as well not bother! It is the equivalent of a +/-4 or 5 on a d20 roll. Aa all-or-nothing mechanic lacks nuance and stifles creativity. It cheapens the game, rather than enriching it.

I'll note that in L&L, although there is math, I've been careful to limit all use of fractions to 1/4, 1/2, and 3/4. That does make it easier. Compare to 5E's one caster level advance for every three class levels in its Arcane Trickster and Eldritch Knight. In a well-designed, rich, and elegant game, the math adds to the play experience, if you do not allow yourself to fear it.

This is part two of a series on elegance in tabletop roleplay games. Part One | Part Two | Part Three