A few weeks ago, I found and wrote about a lion-centaur in an Ethiopian holy text in the British Museum — drawn in the 1940s!

But I figured this HAD to be part of a longstanding tradition, so I went a-searching for more. And I hit some pay dirt!

The blog of the German Historical Institute London has a post written by Dorothea McEwan in 2021, a review of her own book, Ethiopia Illustrated: Manuscripts and Painting in Ethiopia — Examples from the Seventeenth to the Nineteenth Century. Chapter Two of her book has the title, "The Pictorial Representation of Equestrian Saints and Their Victims: A Case Study of St. Claudius and Sebetat." In her post, she describes the chapter as "an in-depth investigation of a composite creature called a 'Sebetat' — a hybrid monster with the head of a human, the body of a lion, and one or two snakes as its tail, with no equivalent in European bestiaries. Sebetat is an evil-doer, although we are not told what he has done."

Not to nit-pick, but yes, there are no sagittaries with double snake tails in European bestiaries. But there are plenty of lion-centaurs, leonine sagittaries, and related drolleries and grotesques in medieval art and heraldry, as I'm blogged about a LOT. But sure, the Ethiopian Sebetat is unique in its evil nature and its snake tails.

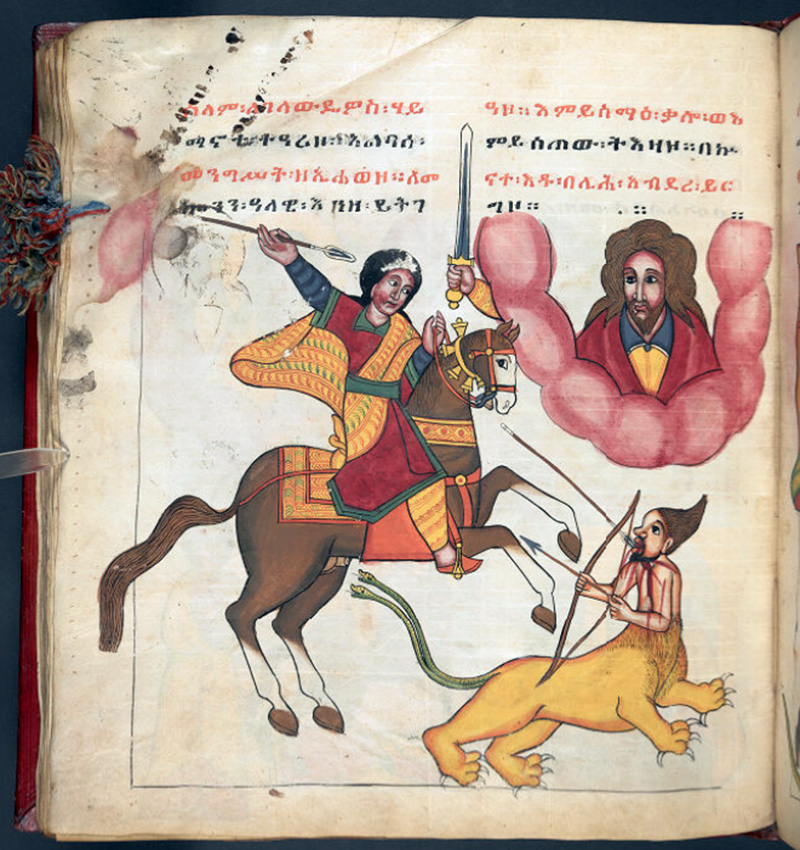

In her blog post, McEwan also offers some delightful art from her book: Fig. 2: 'How St. Gelawdewos Killed the Sobad'at', wall painting, Narga Sellase Church, p. 48.

McEwan has devoted herself to Ethiopian studies, per her biography. She has also written an academic article, "Sebetat: the many lives and deaths of a monster," in the Journal of Ethiopian Studies, Vol. 40, No. 1/2, June-December 2007. In this, she references an 1868 source showing this sketch of a portion of a church door. The caption in the original is "Sebetat, a fabled monster, half lion, half man ... The tail of the Sebetat consists of two serpents, his weapons are bow and arrow."

Interpreting this tradition, McEwan has this to say:

The creature in the middle of the composition, the Sebetat, is a stock figure in Ethiopian painting, visible in wall paintings, manuscripts and icons. The Ara and Persian word 'sabu', lion or beast, suggests a possible link for the name Sebatat. Could this be part of the etymology for Sebetat? On the other hand, the Ge'ez word or name 'Sobada'at' is used for one of the Ba'aflag creatures, that spirits of waters and floods, also signifying serpent or dragon. It is one of serpent creatures in the Christian Roman of Alexander, where it represents one the peoples ruled by Gog and Magog. This in itself does not help us, as the creature on the door has nothing to do with water, but it is a useful pointer to the presence of composite creatures. In English language descriptions, the creature called a 'centaur' or 'a fantastic creature with the head of a lion or leopard and a 'serpent body', a 'monster'. There is no equivalent word for it in English, as there is no composite creature of the Sebetat type anywhere in a European bestiary; it therefore often rendered as 'monster' or 'dragon'.

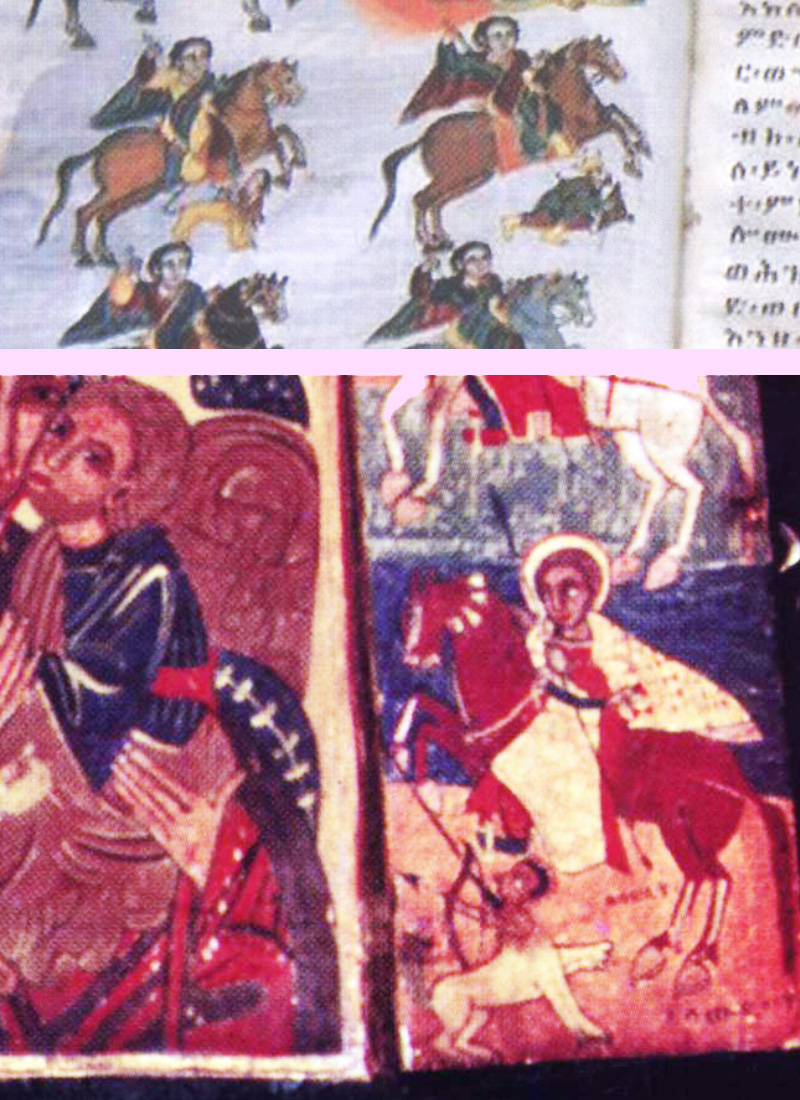

We meet the Sebetat exclusively in scenes with equestrian Saints, notably Claudius, less often St. Theodore or St. Victor, killing a demonic composite creature, and frequently accompanied with the caption 'Sebetat'. The pictorial composition is always the same: whomever the Saint, he always plunges one or two long spears from high on his horse into the body of the creature, an identical motif to St. George slaying the dragon in an act of retribution, a construction of punishment. Three examples of the same scene illustrate his ubiquitous life and death: the first from a wall painting in Narga Selassie [Fig. 6], the second from an illuminated manuscript book, the Darasge Maryam Revelation [Fig. 7] and the third from an icon, where Theodorus is seen killing the Sebetat.

Here are two of those three examples — the third is the same one that she shows us in her German Historical Institute London blog post, reproduced above.

Notably, McEwan points us to another sagittary example, of lion-centaurs in a piece of Arabic art, called "al-qaws." I'm very excited about finding lion-centaurs in another cultural tradition, and I'll dig deeper into this in a future screed.

I highly recommend this paper, if you can obtain access to it, for its detailed delve into the Sebetat and related areas of interest.

McEwan also gave a lecture on the Sebetat in 2010 to The Anglo-Ethiopian Society. In his review of the talk, Geoffrey Ben-Nathan offers more art, goes over points mentioned above, and also says "What does the word Sebetat mean? Nobody knows. In Ge'ez, there is sebad'at but no-one, it seems, knows the correct etymology; it is used for the word 'monster' or 'serpent'. Some paintings even have captions with Sebedat and Sobedat. As Dorothea was quick to say, there is no answer, no hypothesis: 'your guess is as good as mine.' "

Check out two more pictures of sebetats at that link.

I'm especially grateful to Dr. McEwan for her devotion and hard work on this topic. I think she is the academic researcher most interested in lion-centaurs that I have ever come across, in my 25-plus years of searching for info on them.

Following threads from info above, I found another illustrated book at the British Museum, Wisest among the Wise, a book of hymns dating to 1700-1800. On page f. 66v, I found this:

Here's a close-up.

(For those who hate to see a nice wemic impaled through the mouth, I have another version.)

Finally, for the sake of completion, let me mention that the Sebetat has also inspired a musician!